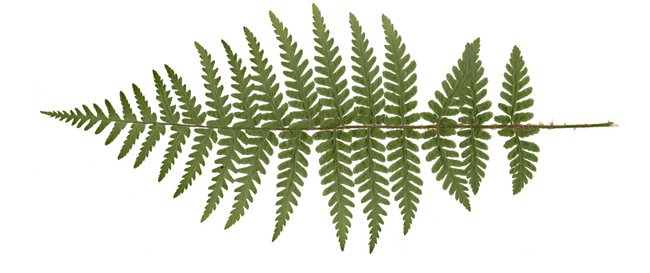

There is a delightful ring to the term “fractal”. It conjures up deep science and a sense of mystery, bringing an impression of wonder. Have a look at the picture of a fern leaf below.

Look at the long shape of the blade, then consider the smaller pinnae (leaflets) branching off from the main stalk, and then observe the pinnules (sub-leaflets) branching off each pinna. The pinnae are smaller versions of the blade, and the pinnules are smaller versions of the pinnae. And finally, each pinnule has lobes branching off the pinnules. The same pattern is repeated at a smaller scale each time. What we have here is a very simple representation of a fractal.

A fractal is a never-ending pattern. They are the result of repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop. This is called recursion, the process of solving big problems by breaking them down into smaller, simpler problems that have identical forms. Fractals are images of highly complex, dynamic systems. Fractal patterns are extremely commonplace in nature. For instance: trees, rivers, coastlines, mountains, clouds, seashells, and hurricanes all follow the fractal pattern we see in our fern example.

What are Fractals?

Fractal geometry helps to understand the complexity within large intricate systems. At school, we were taught Euclidean geometry. Triangles had straight lines and exact angles. Rectangles had 90-degree angles. This is very useful when you design equipment for a factory. But it is not so helpful to help us understand the real world. The problem is, in the chaotic world we live in, there are very few, if any, straight lines and exact angles.

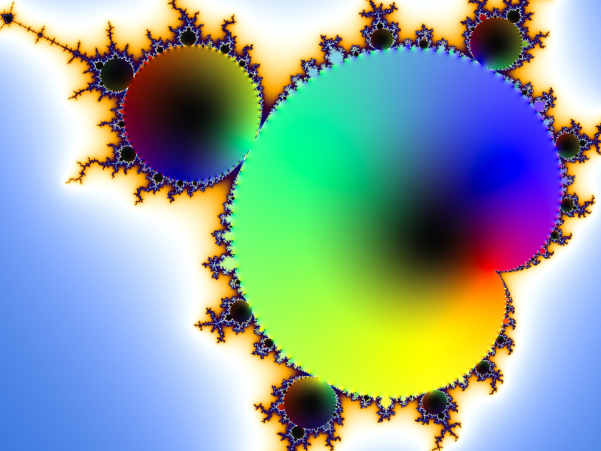

The first inkling of fractals came in the late 1800’s from Karl Weierstrass, a German mathematician. But fractal geometry as a branch of mathematics is with us because of the pioneering work of Benoît Mandelbröt. Mandelbröt worked for IBM in the United States in the 1960s. At that time, IBM was leading the world with enormous computer power which gave Mandelbrot what he needed to explore the bewildering world of fractals.

In this image of the Mandelbröt set we can see the intense multi-layer complexity of fractals, in far more detail than in our earlier fern example.

Parts of your anatomy are fractal, including your brain, your lungs, and your circulatory system. You can see fractals in snowflakes, lightning strikes and waves on the beach. Now that you are aware of fractals you will see them everywhere.Fractal mathematics assists us in understanding the elegant structure within what, at first glance, seems like total chaos.

Fractals in Organisations

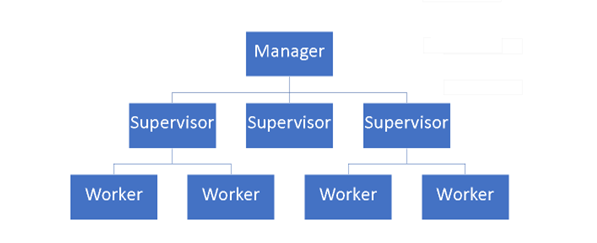

Now, let’s turn our attention to organisations. Plenty of opportunity for chaos here. Most organisations’ structures are presented as Euclidean triangles, such as the one below.

As the organisation becomes more complex, you add new layers to the organisation but retain the triangle structure. But we know from our daily activities that no organisation ever works like this. The neat pyramidal shape masks a much more complex, changeable set of interactions. But we use the pyramid because we have inherited it from the Euclidean past, and besides, the organograms look deceptively neat and elegant. The pyramid organisation possibly has a place in the military, or where team members are inexperienced and need a great deal of direct supervision. But today’s organisations are multiple, changing, complex interactions and interfaces made problematic by power and status.

As the organisation becomes more complex, you add new layers to the organisation but retain the triangle structure. But we know from our daily activities that no organisation ever works like this. The neat pyramidal shape masks a much more complex, changeable set of interactions. But we use the pyramid because we have inherited it from the Euclidean past, and besides, the organograms look deceptively neat and elegant. The pyramid organisation possibly has a place in the military, or where team members are inexperienced and need a great deal of direct supervision. But today’s organisations are multiple, changing, complex interactions and interfaces made problematic by power and status.

The problem is that our management style, our performance management systems, and the way we value our team members are based on the organisation functioning as a pyramid and not as a fractal. No wonder modern organisations are struggling. The fractal can provide us with a new vantage point. We are entering the time of the fractal organisation.

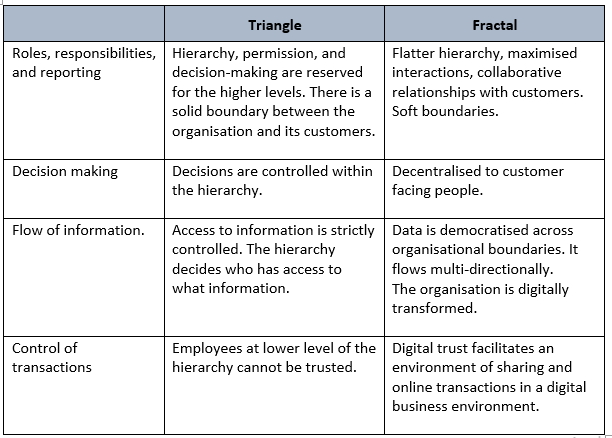

Triangle and fractal organisations rely on fundamentally different organisational principles. It takes more than a few minor tweaks to turn a company designed for a triangle into a company that can successfully exploit fractal advantage. The table below gives a snapshot of some of the more obvious differences between a triangular organisation and a fractal organisation.

How to move to a fractal organisation

There is no clear-cut, tested guideline for transition to a fractal organisation. Right across the world, organisations are working this out. But here are some insights to help you on your way. Put the image of the fern in your mind as you mull over the implications. (The same “shape” at each level.)

- The democratisation of data

Find, collect, clean, and store the enormous amount of data generated by your company’s products or services. Then share this data across the company (subject to confidentiality regulations) so that every employee can access the information to make fast and effective decisions. In addition to operational data, document and facilitate the management of the ideas, insights, and other types of “knowledge” that are generated by team activities. Have an internal repository to store and harmonise this information.

- Limit triangle thinking

Think of your fellow employees as neurons and not as the inhabitants of discreet boxes. They are not endpoints, but pathways to other parts of the organisation.

- Depower the hierarchy

Give more importance to roles (links) and team outcomes than to seniority. Downplay job titles and ranks.

- Embrace fern flexibility

Use the fern as a metaphor. See how you can replicate an integrated fern-approach right to the customer’s doorstep. The separate hierarchies of marketing, sales and production are remnants of the triangle organisation. Think fern.

- Assets are liabilities

Owning the big “things” are no longer important. Think of Asset-as-a-Service. Migrate to local, fast-response service providers that will rent the fixed assets which were once regarded as the core. Logistics, design, and manufacture as examples of where an AaaS solution will help and take a pile of concerns off your shoulders.

- From legal contracts to digital trust

More and more transactions are happening online. You have to trust the e-commerce platform, payment gateway, the broader network of suppliers, and the last-mile delivery system more than you trust your legal department. With more and more transactions within a firm and with external entities and communities, the fractal company has to build trust very differently from the way that triangle companies do. The counter-intuitive requirement is to share information as opposed to keeping it confidential. It’s part of the democratisation of data.

- Bifocal Leadership

Team members in a fractal organisation have two imperatives. The one is to get the job done (as in the triangle organisation). The other imperative is to find new ways of doing the work which may even involve making your current role redundant. You have to build your job, but at the same time, you have to destroy it. It demands a special person to do this.

- Organisational architecture

Here’s a metaphor that sits well with the fern image. Think of a town where the traffic is regulated by traffic lights, and then of another town where traffic is regulated by traffic circles (roundabouts.)

The triangle organisation approach is comparable to traffic lights at a junction. The driver must follow the instructions (permissions) given to them by the traffic lights. Conversely, the drivers in a traffic circle must coordinate their activities with the other drivers around them. The other drivers do not give them instructions but rather they work in concert with each other with a simple set of rules guiding their behaviours. Triangle organisations are full of traffic lights.

Start Now

Triangle organisations hanker after stability. Fractal organisations embody change and embrace chaos. Beginning the process of moving to a fractal organisation is difficult. There is no right way to get started, we are all still working this out. But we all have to start somewhere. Those who can successfully transform their triangle businesses into fractal businesses will be prepared for lasting success in an increasingly fragmented and chaotic world.

.oOo.