Few of us would discount the value of having a diverse workforce. But it is in the method of bringing diversity to our organisations that we find a range of interpretations that befuddle the terrain. A great deal of the debate on diversity centres on physical attributes: race, gender, or disability. It is then a numbers game to adjust the ‘optics’ to meet the prevailing standard of desirability. This is not to say, however, that race, gender, or disability are not gravely important. It is an imperative we cannot escape.

Unintended consequences of a muddled implementation of diversity in an organisation can be an us-vs-them divide, the alienation of the “diverse” individuals, accusations of window dressing and many other manifestations. This is unfortunate because well-meaning attempts to create interdependent diversity have had quite the opposite effect and have left organisations frustrated and tense.

Diversity

A good place to begin to make sense of this conundrum is to attribute a few dimensions to our understanding of diversity. Diversity is not in itself a monolithic concept. We can fracture it into three different facets.

Individual diversity

Internal diversity refers firstly to the characteristics with which a person is born. These include sex, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, or physical ability. Secondly, it includes experiences or circumstances that define a person’s identity such as socioeconomic status, education, marital status, religion, appearance, or location.

Together, these form the “person-ess” of the person. And it is these individual attributes, the “optics,” that are most often considered when contemplating diversity. We see it in authoritarian injunctions: we must recruit more women, black people, or disabled people.

Organisational diversity

Organisational diversity can be found in differences in job function, work experience, seniority, department, or management level. Often, entire departments in a company can be homogeneous —everyone looks the same, comes from the same background, or has a similar experience. We can see this in preferences for recruiting persons with a shared first language or having attended a particular educational institution.

The disadvantage of such a homogenous organisation is apparent in prevailing groupthink. The seeming speed with which such an organisation reaches consensus strangles the innovative, diverging views that are ignored. It is these innovative, diverging views that organisations now most need.

Worldview diversity

Understanding a person’s worldview takes a little bit more effort. Worldview diversity embraces beliefs, political affiliations, culture, and travel experiences. It is how we interpret and view the world.

A diverse set of worldviews, or perspectives, contributes to an innovative, inclusive work environment that is forward-focused. Worldview diversity holds the greatest promise for transcendent organisational success.

The Other

An organisation that has not been successful in institutionalising diversity may find a variety of cleavages running through the organisation. It may be possible to discern a dominant group sharing clearly defined attributes and then an out-group that feels alienated from the overshadowing group. The dominant group may be completely unaware of this and may even criticise the outgroup because of their perceived invalid sense of not belonging.

In sociology, this is referred to as Othering. The Other is an individual who is perceived by the dominant group as not belonging, or as being different in some fundamental way. The process of Othering is the phenomenon in which some individuals or groups are defined as conforming to the norms of the prevalent social group. It influences how people perceive and treat those who are viewed as part of the In-group against those who are seen as part of the Out-group.

Othering in most cases involves attributing negative characteristics to the Out-group, resulting in an “us vs. them” way of thinking about human connections and relationships. Othering is a way of negating another person’s individual humanity and, consequently, those that have been Othered are seen as less worthy of dignity and respect.

To fit in, the Other person must go through a variety of self-negating gyrations to be accepted by the in-group. Black people may alter their speech, opinions, or dress to obtain acceptance in a predominantly white organisation.

Women must negotiate harassment and accusations of emotionality to win respect. in a predominantly male organisation. To make manifest the obvious, a person who feels Other-ed is not going to make the greatest contribution to the success of an organisation.

Metanarratives

None of us is neutral. Our view of the world is made through our upbringing, our education, and our life experiences. This comes together to determine how we see and interpret the world around us. And, naturally, we should seek out people who share similar ways of looking at the world. It is a big-picture lens through which we interpret the world.

A metanarrative is an overarching account or interpretation of events and circumstances that provides a pattern or structure for our beliefs and gives meaning to our experiences.

Our personal metanarrative is the “big picture” spectacles through which we make sense of our world.

A very limited number of metanarratives include Marxism, Freudianism, free market capitalism, enlightenment emancipation, plate tectonics, feminism, evolution by means of natural selection, steady-state equilibrium, and balance-of-nature. Regardless of how well we know these concepts we have our subliminal view on these and many other concepts. And together the collective views on these metanarratives determine how we see the world.

It is therefore obvious that we will seek out the company of those whose metanarratives blend with our own. And in so doing, we may avoid the company of those with diverging metanarratives.

And this is exactly where we make a mistake.

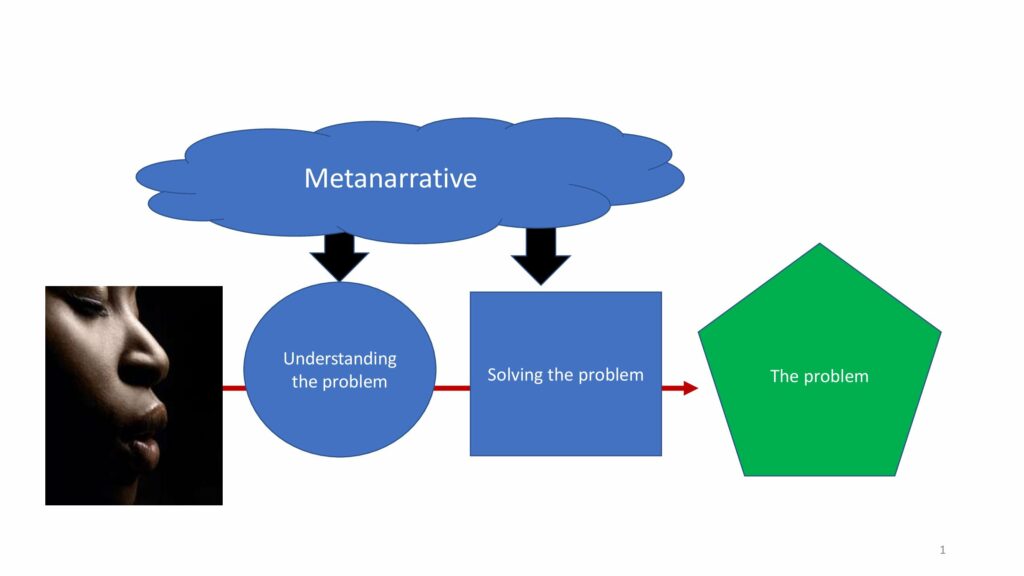

Assume that you must address a problem faced by your organisation. Your understanding of the problem and hence your solution to the problem will be based on your business, technical and interpersonal skills. It will also be influenced by your personal metanarrative, and how you interpret the world around you. It may be depicted as follows:

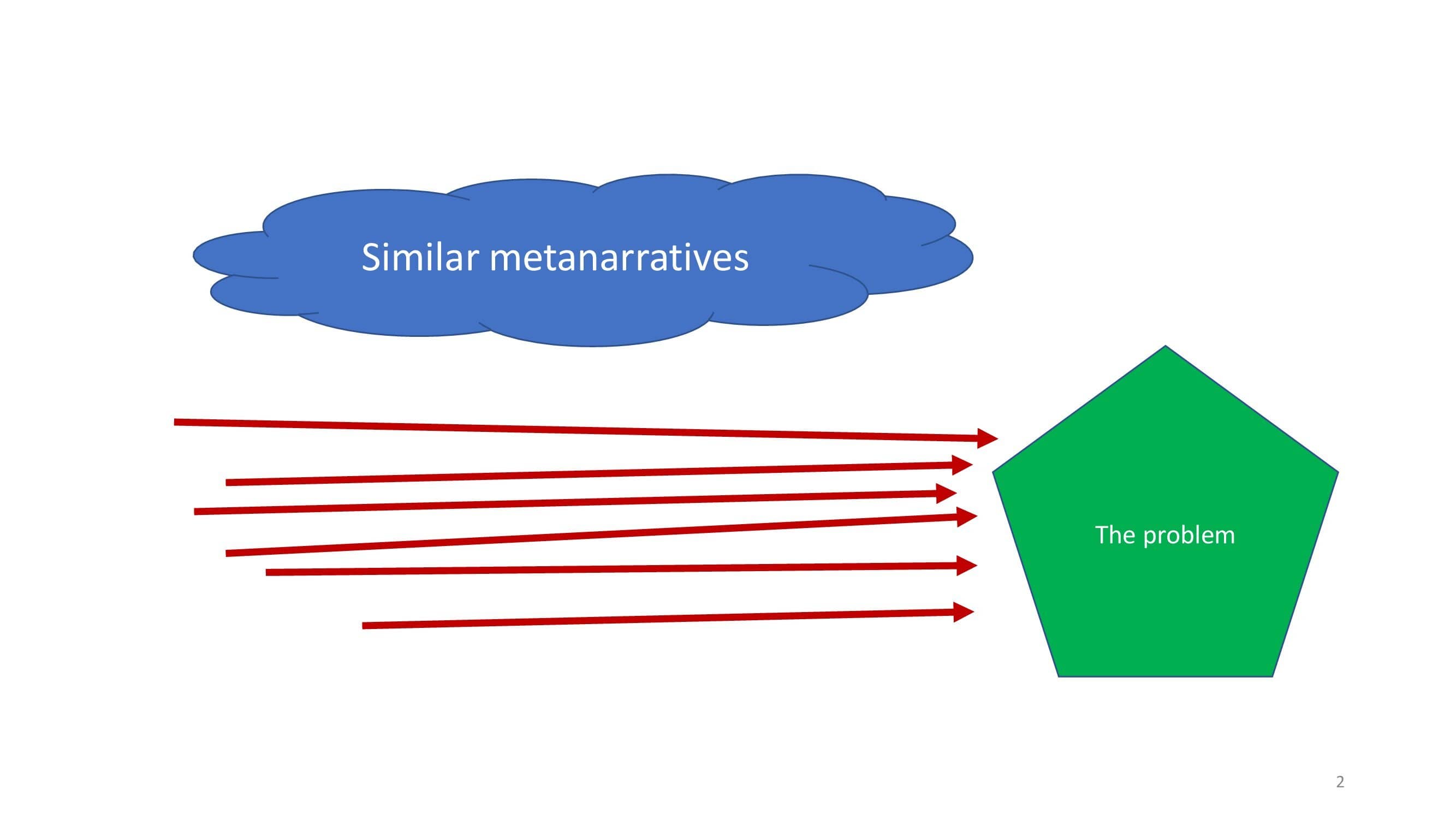

Now assume you are part of a team that shares very similar metanarratives. Your joint approach to solving the problem might be depicted as follows:

You would see the problem in similar ways and come to a consensus, amazed at how quickly you were able to complete the task. But the chances are that your solution might have been a staid, generic one, and which does not radically transform your context.

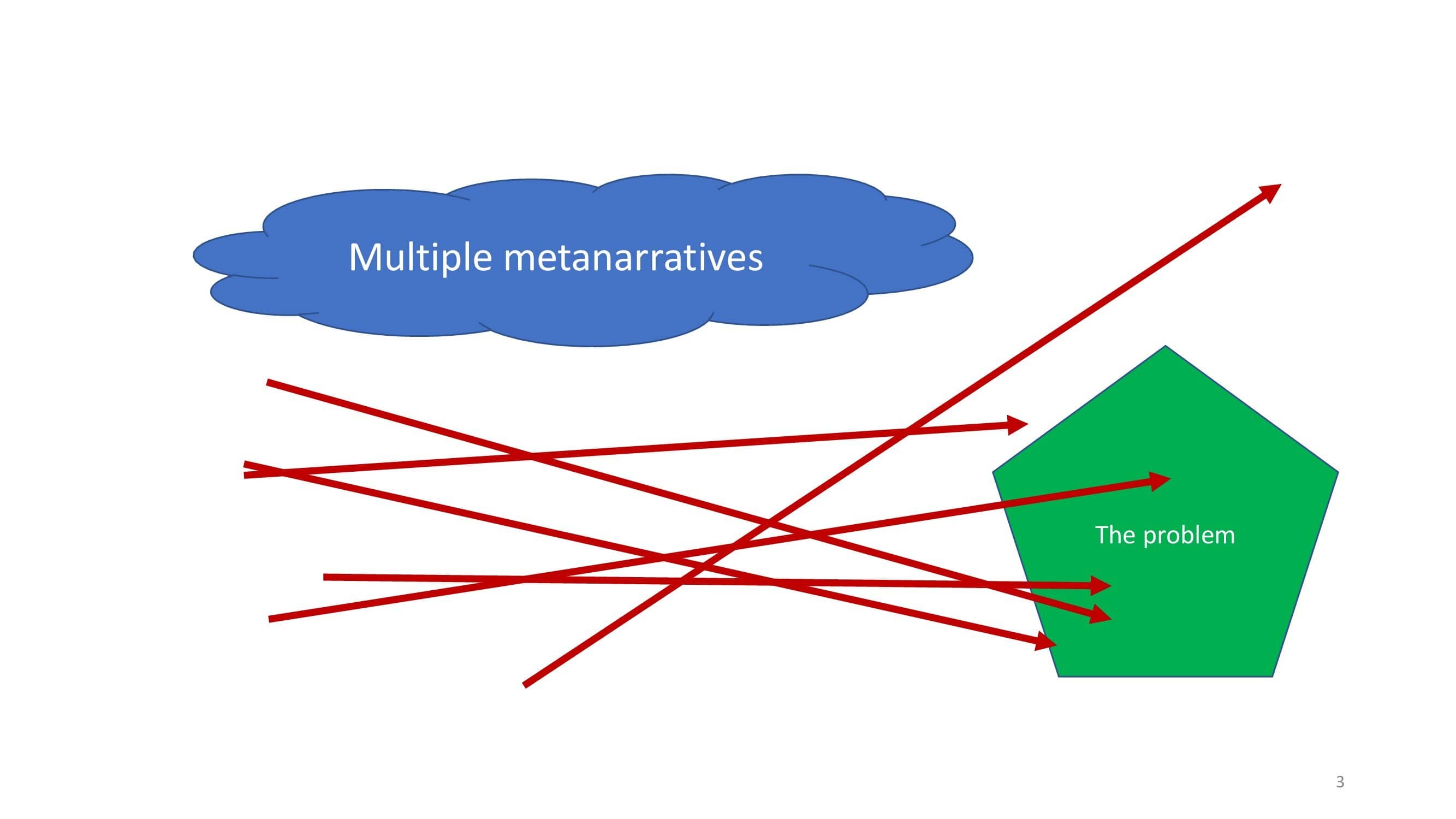

Now consider that you are in an organisation where the Other is not alienated, where the Other is made to feel fully part of the team. You are immersed in a culture of accepting and valuing diverging world views and novel insights. Your approach to solving the problem might look like this.

Immediately you will see a crescendo of novel, unusual and different solutions. Admittedly this may take more time for the various points of view to articulate and be accepted. But the bottom line is that an organisation that is comfortable with differing and indeed opposing metanarratives is going to outperform an organisation that uses a homogeneous approach to managing and deploying its human talent.

A team with many, different, metanarratives will provide a wide range of unique, workable solutions to a problem.

Integrating diversity and metanarratives

Here are some thoughts on harnessing the value of diversity in metanarratives within our organisations:

- Create safe spaces for the team to express and articulate different understandings. Avoid marginalising “other” views.

- Allow different voices to be heard. Don’t shut down exploration to save time. In the long run, it will cost you dearly.

- Pay attention to the silences. When people go quiet, they are either thinking laterally or withdrawing. Either way, you must address this.

- Make it part of the way you work to understand a problem in different ways.

- Recognise that the prevailing culture gets in the way. Go with your gut.

- Break some rules. Just do it. It will feel good.

- It’s OK to disagree. But keep relations intact. Disagreement is the white heat that refines transformative opportunities.

- Run with the radical. Embrace the silly and crazy. It opens the mind.

- Bring the metanarrative into the room. Embrace the metanarrative.

Having a diverse workforce is not just about numbers or quotas or optics, as important as these are. Grasp the truly different. Build a team that thinks the unthinkable.

This is what will distinguish truly excellent companies in the volatile, ambiguous future that awaits us all.