METHODOLOGY

This study utilised Grounded Theory as this a methodology the author used to simply the discovery of emerging patterns in theoretical models through emerging trends in the Media Industry. Grounded Theory is the generation of theories from data, in this study; it is concerned with the Change Management and transformation in South African Organisations. (Glaser in Walsh, Holton et al 2015)

Grounded theory was applied in this study as it is research tool which enabled the author to seek out and conceptualise the emerging Change management and transformational patterns and processes of the relevant and emerging strategic constructs. This methodology was used in developing theory which is more aligned to the emerging change management and transformational trends. This was used by the author as the deductive phase of the grounded theory process (Glaser in Walsh, Holton et al 2015).

1. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparisons of Corporate Culture Taxamomies

Just as people have different personalities, so do organisations have different cultures. Each type of culture has a different effect on the success of the organisation. Some of the many different types of cultures encountered in organisations are as follows:

- Power culture: Usually found in small firms where culture is dependent on a central power source. There are usually few rules and regulations. Power and control lies with a nucleus of a few individuals. If a newcomer is not part of this nucleus or challenges them, sabotage may follow to eradicate the non-conformer.

- Person culture: Where it regards the individual person as a pivot around which the organisation revolves. If this person leaves the organisation it usually has far reaching consequences, both positive or negative. A typical example of this is when Nelson Mandela was the president of SA, He was seen as an opinion leader and people followed him, not always for his political views, but for his charisma. When He stepped down this caused strain on his political party.

- Role culture: Culture is built around defined jobs, rules and procedures and not personalities. People fit into jobs, and are recruited for this purpose. The whole process is logical and rational and is also known as a bureaucracy. This is very much the approach used by the military to ensure stability in the structures as new recruits come and go.

A detailed example of role culture and ISO 9000

Compare what you actually achieve with what is planned and use the information to correct any shortcomings. The overall objective can be described as ‘meeting requirements’ although it does not set these requirements or define the method of meeting them. The design of the standard is such that a considerable

The basic premise here is that without the correct culture ISO 9000:2000 will not operate effectively

ISO9000:2000 is defined as a series of documented standards representing a basic model for Quality Assurance. In its most basic form it requires that you:

Say what you do,

Have documented procedures for performing the work that affects product or service quality.

Do what you say,

Work according to the written procedures

Record what you do,

Retain records of the activities to provide objective evidence of compliance (audit trail).

Improvement,

- Job culture: the organisation is job or project-orientated. Power is through a matrix structure and the emphasis is on getting the job done. This is used predominantly where a single point of responsibility type culture is desired. This is used by many multi-national corporations to control global operations through a centralised head office.

| 1. tough – guy macho culture

Risk taking individualistic

2. Work hard – play hard culture Persistent Sociable 3. Bet – your – company culture Ponderous Unpressurized 4. Process culture Bureaucratic Protective |

1. Power oriented

Competitive Responsibility to personality rather than expertise. 2. Role oriented Legality Legitimacy Pure bureaucracy

3. Task oriented

Competency Dynamic 4. People oriented Consensual Rejects Management control

|

1. Power culture

Entrepreneurial Ability value

2. Role culture Order Dependable

3. Achievement culture

Personal Intrinsic motivation 4. Support culture

Mutuality Trust |

1. Barbarian

Ego – driven Workaholic

2. Monarchial Loyalty Doggedness

3. Presidential

Democratic Hierarchical 4. Pharonic

Ritualized Changeless |

| Authors:

Deal and Kennedy (1982) |

Williams et al. (1989) Harrison (1972) Handy (1980) |

Schein (1990) |

Graves (1980) |

| Dimensions:

Amount of risk (High/Low) Speed of feedback (Slow/Fast) |

Formalization (High/Low) Centralization (High/Low) |

Individualistic/ Collectivistic Managerial/Ego Drive |

Bureaucratic/Anti – Bureaucratic |

CULTURE AND STRATEGY

“Dream big dreams. Set lofty goals. Then . . . put yourself into a position to attain them.”

Ted Turner

“You’ve got to have concern for what your people do.”

Hewlett

Those entrusted with leading global corporations into the 21st century faces an environment of rapid change. Issues such as competitive pressures, globalisation of markets as well as an increasingly sophisticated and diverse customer base is only some of the issues that need to be dealt with in an effective manner. All this is also taking place as the global workforce becomes more diverse with changing values and expectations. As a result of these developments, it has become clear that business strategy should be developed in a more creative and flexible way (Lattimer in Thomas, 1996:16).

According to Brown (1995) the concepts of strategy and strategic management have received increasing attention in recent times. The importance of strategy has been highlighted by the notion that culture and organisational effectiveness is related and that strategy is a cultural artefact with symbolic meaning and association for employees. Strategy does not merely reflect or externalise culture but shapes it. There is no commonly held view of the definition of what strategy is or how it should be defined.

Ashdown (1998) suggests that there are three basic approaches to strategy formulation. Firstly there is a focus on operating and structure which focuses on gaining insights from the resolutions of today’s problems and the evaluation of the effectiveness of today’s operations. In terms of structure an attempt is made to understand the industry, price and competitor dynamics, with the intention of understanding the wider operating environment, competitive structure, and being able to change and adapt.

Secondly there is a medium term view that is future focussed, a view that develops scenarios, studies industry evolution and analyses competitor strategy. This approach is about gaining insights into factors that are critical for the future success, choosing them and designing the organisation with the appropriate capabilities.

Griffith (1963), Wee Chou Hou, Sheang & Hidajai (1991) and Min Chen (1994) all comment that the former approaches to characterise a systems of management and a ‘militaristic’ view as advocated in Sun Tzu’s “The art of War“. These approaches are also about formal, explicit plans devised by senior executives. Mintzberg (1987:66) argued that the formulation of strategy was not dissimilar from a potter’s crafting activity. ” The planning image, long popular in the literature, distorts these processes and thereby misguides organisations that embrace it unreservedly”. He argues that the ‘crafting’ is a process that integrates a future focus with patterns of the past and that the strategy is not necessarily deliberate but can emerge and can form, as well as being formulated.

The third approach is also future focused but is more concerned with the organisation’s behaviour and culture in the longer term. Use is made of a dataless planning approach with the rationale that a clear vision of a desired future is the key to the gaining of insight. It engages with the ‘creative sub-conscious’, individuals convince themselves, cognitive dissonance is created and there is a release of energy. Further, according to Senge (1999), this approach aims to develop ‘organisational learning’ through the creation of a culture in which insights are developed, defensive routines are eliminated and new insights substituted.

There is a close fit between culture and strategy. To implement and execute a strategic plan, an organisation’s culture must be closely aligned with its strategy. By understanding this strategic/cultural fit the strategy-makers can select a strategy compatible with the ‘sacred’ parts of the prevailing corporate culture.

While there are difference in the notions of strategy, there is a common ground with culture to the extent that strategy is a system of managing and a ‘craft’ activity. “Culture and strategy are said to guide expression and interpretation, they are retrospective, summarising patterns in the past decisions and actions…they provide continuity and identity and a consistent way of ordering the world” (Brown 1994:168). Of importance is not the degree to which culture and strategy are the same phenomena, but the extent to which this might impact on organisational effectiveness.

Schien (1983) also argues that if we take organisational seriously, we will help management recognise that cultural assumptions dominate managerial thinking about strategy, structure and systems and not to focus on style and people. Riemann & Wiener (1996) note that the literature reflects a view that corporate culture can be a ‘double edged sword’. A strong culture can be vital to an organisation, but only if it is the ‘right’ one for its evolving mission and strategies. This suggests a need for alignment.

Tosti (1995) outlines a model suggesting firstly that strategy is about what an organisation needs to be ding, goals, objectives and the activities to achieve these stated ends and secondly, culture is about how things should be done, the values, behaviours and practices. The degree to which the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ converge or are aligned will determine the extent of success. Organisational alignment consists of compatibility between the strategic and cultural ‘paths’ and consistency within them. Porter (1990) describes this in terms of the right asset mix in conjunction with the right mix of values and patterns of behaviours. Further, if this is to be unique to the ortganisation then it is likely that the difference will be in respect of the organisation’s culture.

Rossiter (1989:14) in making a case for using culture to build winning organisations, quotes Thomas Watson Jnr, Chairman of IBM, as saying, “I firmly believe that any organisation, in order to survive and achieve success, must have a set of beliefs on which it premises all it’s policies and actions. Next I believe that the most important single factor in corporate success is faithful adherence to those beliefs…”. The suggestion that culture on its own is the determinant of performance is far from conclusive. Rather it is one of a number of interrelated components that collectively contribute to the organisation’s success. It generates dynamics that, in turn affect the strategy and then impact performance

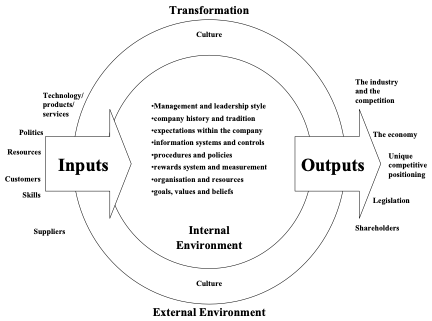

INTEGRATED MODELS SHOWING COMPANY CULTURE AND STRATEGY

Source: Adapted from Smit P, De J Cronje G, (1997)

Building a successful strategy – why culture is such an important strategic variable.

Building a successful strategy – why culture is such an important strategic variable.

Every organisation has a unique organisation culture, its own business philosophy and principles. It has its own ways of approaching problems and making decisions, it’s own embedded patterns of “how we do things around here.” It has it’s own lore (stories told over and over to illustrate company values and what they mean to employees), it’s own taboos and political don’ts – in other words, it’s own ingrained beliefs, behaviour and thought patterns, business practices, and personalities. If one studies companies with strong organisational cultures that are successful in creating and implementing strategies such as McDonald’s where the bedrock of the organisations culture dedicated to customer satisfaction, quality, cleanliness and value: employees are drilled over and over on the need for attention to detail and perfection in every fundamental of the business. This reinforces and strengthens the organisational culture. Over time, these cultural underpinnings come to be shared by the organisations managers and employees and then persist, as new employees are encouraged to adopt and follow the professed values and practices. An organisations culture is the product of internal forces; it represents an interdependent set of values and behavioural norms that prevail across the organisation. This in turn enhances the building of a strategy-supportive organisational culture needed for successful strategic implementation because it produces a work climate and organisational spirit that thrives on meeting performance targets and being part of a winning effort. Cultures are perpetuated as new leaders act to reinforce them, as new employees are encouraged to adopt and follow them, as legendary stories that exemplify them are told and retold, and as organisational members are honoured and rewarded for displaying the cultural norms. This ensures effective strategic implementation will be more effective.

Building a successful strategy – why “organisational culture” is so important.

But beware of the embedded strengths and weaknesses of organisational culture.

Organisational cultures may vary widely in strength and in makeup. Some cultures are strongly embedded which, while others are weak and fragmented in the sense that many subcultures exist. Strong, inwardly focused cultures are often not open to change and often cause the company performance to decline. Strong high-performance, adaptive cultures make champions out of people who excel. This breeds innovation and competition within the organisation and can be extremely beneficial to designing and implementing strategies in an innovative business environment such as 3M who encourage staff the “bootleg” and take time away from their normal duties to work on new and unauthorised projects. Steve Jobs the CEO of Apple Computers said it best: “The role of a good leader is to create a clear vision and articulate that vision to the people around you and ensure they understand it. When they do they will work out what they need to do to achieve this shared vision and how to do it. The premise it that there must be a strong, innovative and supportive culture in the organisation.” Peters (1985: 126)

Weak, fragmented cultures, will hinder consensus on strategic creation and implementation as few values and behaviourial norms are shared company-wide, and there are few strong traditions to bond the organisation towards a common goal.

Best you fully understand organisational culture, as it may be a liability.

From the definitions and discussion so far it is evident that organisation culture enhances commitment and consistency of employees behaviour. These are clearly benefits to an organisation as it reduces ambiguity and tells of how things are done and what’s important. But beware, we shouldn’t ignore the potentially dysfunctional aspects of culture, especially a strong one, on the organisation’s effectiveness.

According to Robbins (1998: 602) Organisational culture may be a liability in terms of being a barrier to change where the shared values are not aligned to those that will assist the company to create a competitive advantage in the marketplace. This is often a major cause of programs such as Total Quality Management to fail. Companies such as IBI with strong cultures have struggled to adapt to a dynamic environment resulting in loss of market share to companies such as Apple computers with a culture that can adapt faster to market forces. Peters (1985)

Organisational culture may be a liability in terms of being a Barrier to diversity, where strong cultures put pressure on employees to perform and often result in a loss of valuable skill. This is a lesson learned by Texico where the range of values and styles were limited by a strong culture that condoned prejudice. This resulted in the formal corporate diversity policies being violated Robbins (1998: 602)

Organisational culture may be a liability in terms of being a Barrier to mergers and acquisition. The historical basis for evaluation of mergers and acquisitions has been financially based. This has turned out to be a very misleading approach if it is the sole basis for the decision. A number of mergers and acquisitions have already failed or showing signs of failing due to conflicting organisational cultures. This can be seen in cases such as Citigroup, acquiring City bank. The CEO, John Reed is currently still trying hard to make the merger of cultures work but as he states “I will tell you it is not simple and it is not easy, and it is not clear to me that it will necessarily be successful.” In his discussion he likes this to a body that rejects implanted parts and creates an unusual, strange, aberrant behaviour. This leads to uncertainty between cultures and has an adverse effect on achieving the organisation’s goals. This leads to a lack of trust and as was the case on the Time Inc’s merger with Warner communications, the intended synergies were never realised. Robbins (1998: 602)

Organisational culture and it’s Effect on company profitability, performance and productivity

Although the performance of an organisation is directed towards need satisfaction, one of the primary objectives is still to make a profit. Profitability is one of the yardsticks that the business world uses to measure an organisation’s performance.

Fulop (1999)

To tie in with the principles of profitability, the concept of productivity also merits attention. The cultural and behaviour characteristics of an organisation have a profound effect on performance – hence profitability and productivity. A low growth in productivity is a reflection of the morale of the organisation. Any efforts to increase productivity are doomed to failure in the absence of a total commitment to objectives as well as an organisational culture that underscores such objectives.

Barney (1986) has examined the relationship between culture and ‘superior financial performance. He argues that sustained superior financial performance requires sustained competitive advantage. Barney concluded that culture can, and does, generate sustained competitive advantage, and hence long-term superior financial performance, when three conditions are met.

- The culture is valuable.

- The culture is rare.

- The culture cannot be easily copied by competitors.

Organisations that have strong and unique cultures generally experience excellent performance. Why?

- Consumers are attracted not just to products, but to the entire communication environment around their purchases, and to the idea of supporting a company whose values and styles they respect.

- Employees are much more likely to want to work for companies that they feel proud of what they do, and where they feel that they enjoy a distinctive work experience. For example, a recent study by a foodservice industry group found that workers named organisational culture factors as some of the strongest motivators in terms of staying in their jobs. Even if they could get a few more dollars at a restaurant down the road, respondents said that factors such as feeling that the company is well managed and having a boss who is moral would cause them to stay where they were.

- Certain kinds of organisational cultures promote learning and information sharing. In these environments, much less investment in formal training is necessary, and the investment that is made is much more effective. The same goes for job performance, where there is a general ethic to work hard and to be dedicated, fewer external incentives and policies are needed to ensure that employees do what’s expected of them.

Dorbyl moved out of its massive Dorbyl Park headquarters in Bedfordview and into offices for all the staff of 17 in Parktown at the end of March 1997. The move was seen as symbolic of the end of the old company. A profit-driven culture was introduced and those parts of its business which did not achieve appropriate returns have been sold.

Source: Financial Mail, 7 February 1997, p 70.

REFERENCES

Allaire, Y. & Firsirotu, M.E. 1984. Theories of Organisation Culture. Organisation Studies, 5(3), 193 – 226.

Ashdown, A. 1998. Notes on Strategic Planning. Unpublished handout. Management briefing.

Beck, D. & Linscott, G. 1991. The Crusible: Forging South Africa’s Future. Johannesburg; New Paradigm Press.

Bennis, W. & Nanus, B. 1985. Leaders: the strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper and Row.

Biesheuvel, S. 1987. Cross Cultural Psychology: Its relevance to South Africa. In K.F. Mauer & A.J. Retief (eds). Psychology in Context: Cross cultural research tends in South Africa. HSRC Investigation into Research Methodology. Research Report Series 4. Pretoria HSRC. 1 – 35.

Bridges, W. 1992. The character of Organisations using type in organisational development. CPP Books.

Brown, A. 1995. Organisational Culture. London. Pitman Publishing.

Dalton, M. 1959. Men who Manage. New York: Wiley.

Deal, T.E. & Kennedy, A.A.1982. Corporate Cultures. Massachusetts: Addison.

Denison, D.R. 1996. What is the difference between organisational culture and organisational climate? A natives point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Academy of Management Review, July 21 (3), 619 – 654.

Drennan, D. 1992. Transforming Company Culture. London: McGraw – Hill.

Eldridge, J.E.T. & Crombie, A.D. 1974. A Sociology of Organisations London: Allen and Unwin.

Fulop, L & Linstead, S. 1999, Management, A critical Text. Macmillan Business.

Glick, W.H. 1985. Conceptualising and measuring organisational and psychological climate: Pitfalls in multilevel research. Academy of Management Review, 10, 601 – 616.

Godsell, G. 1981. Value Conflicts in Organisation. National Psychology Congress, September. Cape Town.

Graves, C.W. 1970. Levels of Existence: An open system theory of Values. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 10 (2), 135.

Harrison, R. 1972. Understanding your organisations character. Harvard Business Review, May – June, 119 – 128.

Hofstede, G., Neuwen, B., Ohayv, D.D. & Sabders, G. 1990. Measuring organisational culture: a qualitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 286 – 316.

Hysamen, D. 1996. Re – humanising the organisation. People Dynamics, 14(8) 34 – 39.

Jahoda, M. 1979. The impact of unemployment in the 1930’s and the 1970’s. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society. 32, 309 – 314.

Jacques, E. 1951. The changing culture of a factory. New York: Dryden Press.

Kantor, l., Schomer, H. & Louw, J. 1997. Lifestyle changes following a stress management programme: an evaluation. South African Journal of Psychology, 27 (1), 16 – 21.

Kroeber, A.C. & Kluckohn, C. 1952. Culture: a critical review of concepts and definitions. New York: Vintage Books.

Moola, M.A. 1998. The relationship between organisational culture, values and need systems. Unpublished D. Comm Thesis. University of Durban Westville.

Myers, M.S. & Myers, S.S. 1974. Toward understanding the changing work ethic. California Management Review, 16(3), 7 –19.

Paconowsky, M.E. & O’ Donnell – Truillo, N. 1982. Communication and Organisational Culture. The Western Journal of Speech Communication, Spring, 46, 115 – 130.

Peters, T.J & Waerman, R.H. 1982. In search of Excellence. New York: Harper and Row.

Pietersen, H. 1991. Corporate Culture: clarification of a concept. Human Resource Management, 6(10), 26 – 31,

Robbins, S.P. 1996. Organisational behavior: Concepts Controversies Applications. 7th Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Robbins, S.P. 1999. Downsizing of organisations – psychological aspects. Journal of Management Education. February, 23 (1), 31 –41.

Robbins, S.P. 2001. Organisational Behaviour, 9th Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Ribinson, R.J. 1987. The mediating effect of organisational climate on personal growth amongst quality circle members. Unpublished Masters Thesis. University of Cape Town.

Roger, R.W. 1995. The psychologecal Contract of Trust – part III. Executive Development, 8(2), 7 –15.

Schein, E.H. 1990. Organisational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey – Bass Publishers.

Schmickl, E. 1985. Organisational Culture. Unpublished Paper. S.B.L. UNISA.

Segall, M.A. 1984. More than we need to know about culture, but are afraid to ask. Journal of Cross – Cultural Psychology, 15, 153 – 162.

Selznick, P. 1957. Leadership in Administration. New York: Harper Row.

Smith, L. 1994. Burned or Bosses. Fortune. 25 July, 108 –113.

Smit P, De J Cronje G, (1997) Management Practices: A Contemporary Edition of Africa, (2nd Ed) Juta.

Tagiuri, R.1968. The concept of organisational climate. In R. Tagiuri & G. Lituin (eds) Organisation Climate: Explorations of a Concept. Boston: Harvard Graduate School of Business.

Thornhill, A., Lewis, P., Millmore, M. & Sauders, M. 2000. Managing change – a Huamn Resource Strategy Approach. Harlow: Prentice Hall

Wee Chou Hou, Lee Kai Sheang & Bambang Walujo Hidajai 1991. Sun Tzu: War and Management. World Executives Digest, November, 3 –4.

Weisbord, M. 1987. Organisational Diagnosis: A workbook of Theory and Practice. Reading:Addison – Wesley Publishing Company.