Those of us who have had the opportunity of tertiary education sometimes forget how privileged we have been. For many fortunate people, the chance to go to a university and study the qualification of their choice is a foregone conclusion. They went to good schools, they obtained suitable school examination results and they had parents who could afford to pay the fees and provide board and lodgings. Once they have the qualification, they tend to mix with and work with similarly qualified people. And their children, in turn, go to the right schools and then go on the same kind of post-school studies.

And so, the pattern is laid down in our society, a self-replicating elite has access to the better jobs and opportunities, and an underclass, who are held back because they do not have the resources and opportunities to carve out a career that is commensurate with their aptitudes and abilities.

Can we stand by as this state of affairs perpetuates itself? Is it reasonable? Is it fair? And of course, we have to say no. We cannot allow people with potential, to be kept out of the mainstream of public endeavour, purely because they are poor and cannot afford education.

To help us understand more about this, let’s pull back the lens and look at education from a number of different points of view.

From a human rights point of view, there are three rights to education.

There is the right to education. This means that education must be available and accessible to those who need it and those who wish to study.

A second right is the right in education. Learners, of whatever age, must have educational choices available to them, and the education must be of an acceptable nature. The education they receive must meet accepted quality standards, and the language of instruction must not be a barrier to entry.

The third right is the right through education. This is the outcome of education. Education must produce competent citizens, to enjoy the rights and obligations of citizenship in their countries. This has to take place in a society where there is no child labour, no child marriage and children are not forced into war.

And yet, when we look around us, we see a world where these rights are honoured in the breach. An unenforced right is not a right at all.

Let us now look at education through the lens of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The Agenda lists seventeen Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs as they have become known. The 193 member states of the United Nations came together and made a commitment to eradicate poverty and achieve sustainable development by 2030 world-wide. The Agenda is a plan of action to improve the situation of people, the planet and to promote prosperity.

Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) is the education goal within the 17 SDGs. It aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

SDG 4 is made up of 10 targets. We will consider two of these targets, as they are most appropriate to our current purpose:

Target 4.3 By 2030, the target is to ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university. [emphasis added]. This target goes further and argues that barriers to education should be removed. It particularly speaks to university education and the provision of lifelong learning opportunities for youth and adults. It states that “the provision of tertiary education should be made progressively free, in line with existing international agreements”.

Target 4.4 speaks to increasing the numbers of young people and adults relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, so that they can take employment in decent jobs and entrepreneurship.

With regard to access to education the target argues that “Learning opportunities should be increased and diversified, using a wide range of education and training modalities, so that all youth and adults, especially girls and women, can acquire relevant knowledge, skills and competencies for decent work and life”.

With regard to skills acquisition, the following is put forward: “Skills acquisition: Beyond work-specific skills, emphasis must be placed on developing high-level cognitive and non-cognitive/transferable skills, such as problem-solving, critical thinking, creativity, teamwork, communication skills and conflict resolution, which can be used across a range of occupational fields”.

So, in short the SDGs argue for the following in education:

- Cost appropriate access to education.

- Lifelong education which produces informed, discerning adults and to be good citizens contributing to society.

- Education in the full range of practical, human and thinking skills to enable citizens to fulfil substantive roles in their places of employment

We can see an overlap between the human rights reasoning and the targets of the SGDs.

The World Bank released a report on South Africa in 2019, which pointed out that enhancing South Africa’s socio-economic inclusion through increasing equitable access to the country’s tertiary institutions in a weak economic environment will require comprehensively improving the country’s post school education and training system.

Paul Noumba Um, World Bank Country Director, made this comment in the report:

“The importance of acquiring skills to enable South African’s youth to find jobs and earn higher wages thereby alleviating poverty, income inequality and joblessness, makes the policy to enrol more students in tertiary institutions a must, but in an environment of weak growth this is a challenging proposition which requires making some difficult trade-offs,”

The report acknowledged that the state is unable to be the main provider of post-school education and training [PSET]. It argues for greater private sector involvement with a less onerous accreditation regime, and ways of ensuring greater equity in supporting students.

The former UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, expressed the situation very crisply:

“We cannot have young people growing up without the knowledge, skills and attitudes to be productive members of our society. Our societies cannot afford it. And neither can business. Business needs a creative, skilled, innovative workforce. And investing in education creates a generation of skilled people who will have rising incomes and demands for products and services – creating new markets and new opportunities for growth”.

Source: Ban Ki-moon – The Smartest Investment: A Framework for Business Engagement in Education. 2013

Let’s look at the right to education from a vantage point closer to home.

South Africa’s Bill of Rights has long been hailed as a leading document of its kind. The South African Constitution protects the rights of all South Africans and the Bill of Rights, in Section Two of the Constitution, spells out these rights. This Bill of Rights is a cornerstone of democracy in South Africa. It enshrines the rights of all people in our country and affirms the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom.

Section 29.1.b of the Bill of Rights expresses it thus:

“Everyone has the right to further education, which the state, through reasonable measures, must make progressively available and accessible.”

A careful reading of the text will demonstrate that the burden of providing further education should not be borne alone by the state but that the state should make access to further education “progressively available and accessible.”

The ‘rights’ aspect is only one side of this matter. Let’s consider it from a business and economic point of view.

Most of the time we regard investment in education as a kind, socially responsible act, to demonstrate what good corporate citizens we are. There is however a compelling business case to be made for investment in education, particularly at the post school level.

Appropriate post-school education equips individuals with knowledge and skills critical to sustainable development and economic growth. The more that young adults have the opportunity to reach their potential, the better it is for the economy.

Better educated adults bring enviable advantages. Critical thinking, communication and problem solving improve business operations and reduce conflict. Numerous studies have shown that the better educated women are in a society, child mortality and conflict decrease. A skilled workforce improves productivity and drives business growth.

Improved education is linked to increases in individual wages and economic growth. One additional year at school can increase a woman’s earnings by 10 to 20 per cent.22 This creates societies with more disposable income for goods and services while strengthening women’s empowerment in families and communities.

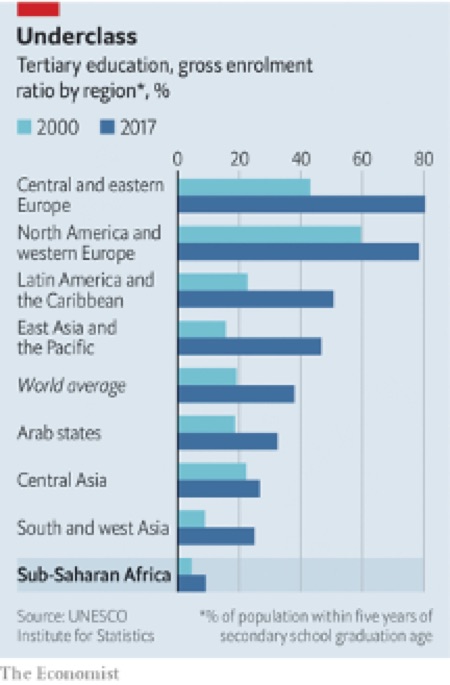

This graph below from the Economist, illustrates that less than 10% Africans get to university, or some form of tertiary education.

Source: The Economist

Source: The Economist

The Economist builds out their argument as follows:

“In the poorest African countries, it costs 27 times more to fund a university place than one at primary school. Since students typically come from affluent families, university spending subsidises the children of elites. In Ghana, the higher-education spending that goes to the richest tenth of households is 135 times that spent on the poorest tenth. Policymakers find themselves deciding whether to spend scarce resources on helping poor children attend a school or rich children go to university.”

The Economist reports that from 1990 to 2014 the number of public universities in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 100 to 500, while private universities grew from 30 to more than 1,000. And there is still room for many more.

Students at private universities often benefit from new ways of teaching. Regenesys, operating in South Africa and Nigeria, has a strong online model for education delivery.

The Economist points out that the biggest barrier to expanding access to tertiary education is student financing. ……”This is not just an injustice but a sign of economic inefficiency. The average gap between wages earned by graduates and non-graduates in sub-Saharan Africa is wider than in other regions. It would make sense if students could defer the expense.”

And therein lies the rub. The biggest barrier African adult students experience in obtaining access to education is the high up front cost of education. If this cost can be spread out over a lifetime of earning, the opportunities for entry rise dramatically. The second biggest barrier is access. And this can be overcome by online learning, provided that the cost of internet access can be brought down.

Africa boasts a number of examples where innovative individuals and organisations have created access opportunities to quality education. They have challenged the problems of cost and access and have developed unique solutions.

Kepler

Kepler is a non-profit higher education program that operates a university campus in Kigali, Rwanda, in partnership with Southern New Hampshire University. SNHU provides students in East Africa with access to accredited American degrees through their innovative competency-based online degree. The goal of the unique Kepler approach is to lower the cost of higher education without a reduction in academic quality or outcomes. The online work is paired with extensive support services provided by Kepler, which include in-person coaching, health and financial support services and career preparation.

Ashesi

Ashesi is a private, non-profit university in Ghana. It combines a rigorous multidisciplinary core with degree programmes in Computer Science, Business Administration, Management Information Systems, and Engineering. Ashesi has a track record in fostering ethical leadership, critical thinking, an entrepreneurial mindset, and the ability to solve complex problems.

Regenesys Business School

The Regenesys Education For All (Ed4All) is a game-changing, innovative and technology-driven initiative, which disrupts traditional higher education systems and provides access to affordable and quality higher education. Regenesys has campuses in South Africa, Nigeria and India, but because of their unique online learning capability, they offer their programmes worldwide.

Ed4All allows qualifying matriculants to obtain their first degree at the cost of R500 per month for three years. Following this, the Foundation aims to place graduates in jobs within six months of graduating. Once employed, the candidates’ pay back the outstanding funds according to their circumstances, which is then used to educate new students in need. Students pursue accredited business-related academic qualifications like the Higher Certificate in Business Management (HCBM), Bachelor of Accounting Science (BCompt), Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA), Postgraduate Diploma in Business Management (PDPM), and Regenesys’ flagship programme – the Master of Business Administration (MBA).

The African Leadership University

The African Leadership University is a network of tertiary institutions with operations in Mauritius, Rwanda and Kenya. Its mission is to build 25 campuses across the continent and produce three million young African leaders over the next 50 years. It is part of the wider African Leadership group, with the aim to reinvent high school, university and graduate education in Africa. The ALU programme focuses on 21st-century skills, personalised learning, values and character, career development and work experience, and creating a network for graduates. ALU students spend four months of each academic year in an internship in an organisation on the continent. African Leadership group was founded by Fred Swaniker, a Ghanaian African leadership development expert and Stanford Business School educated social entrepreneur, in 2004.

The Akilah Institute

The Akilah Institute is a non-profit college for women in Kigali, Rwanda. The Institute offers three-year diplomas in entrepreneurship, hospitality management, and information systems. Akilah’s mission is ”to offer a market-relevant education that enables young women to achieve economic independence and obtain leadership roles in the workplace and in society.”

Chancen International

Kepler and Akilah, an all-female college in Kigali, are working with Chancen International, a German foundation, to try out a model of student financing popular among economists—Income Share Agreements. Chancen pays the upfront costs of a select group of students. Once they graduate, alumni pay Chancen a share of their monthly income, up to a maximum of 180% of the original loan. If they do not get a job, they pay nothing.

End Note

Tertiary education faces many challenges in Africa. Access to education. Access to funding. Access to education of the kind that builds the economy. Any investment in a business qualification is a worthwhile one, as the skills learned can be applied across a range of sectors and operations – from NGOs to manufacturing companies, from financial institutions to agriculture.

We have seen how several institutions have created unique pathways to opening education to those who need it, and those who can make a contribution to the economy. Human rights documents, and policy statements have no value unless they are translated into action. It’s up to us, who have had the advantage of excellent post school education, to unlock the opportunities for others.

Read also: Poverty in Africa: The way out!

1 Comment

I WOULD LIKE TO ENROLL MY DAUGHTER TO STUDY LLB. I HAVE INFORMATION FROM SOMEONE THAT I CAN PAY ANY AMOUNT THAT I CAN AFFORD FOR HER TO FURTHER HER STUDIES.

KINDLY ADVICE.

REGARDS

ANNELIEN VAN DER BYL